From the Georgian period to the Victorian,

the rich continued to eat grandly, but it was the middle classes, and the upper

working class that really felt the benefit of industrialization when it came to

eating. The kitchen technology recommended to the poor by Soyer and his

contemporaries was just the thing for those classes with new spending

power who were keen to climb the social ladder. As well as increased wealth in

the expanding middle class, there was far more available to buy. Industrial advances

meant that food could now be tinned to last what must have seemed ages to

people used to fast spoilage; pre-made powders for eggs, custard, chocolate and

spices like mustard continued to remove toil from food preparation; and new and

exciting flavours could be bottled and sold as sauces – many of them by

companies and brands still going strong today.

|

Not actually Victorian-era artefacts |

One of many, many editions of Mrs Beeton's collection

Eliza Acton was the first, a woman who

began as a teacher and poet before publishing Modern Cookery in All Its Branches for Private Families in 1845.

Her carefully-considered, tried and tested recipes were ideal for the novide to

follow, as she included a novel idea – an itemised list of ingredients and

measurements at the end of each recipe. This was the first time anyone had done

that, and she was widely copied – not least by Mrs Beeton, who moved the list

strategically to the start of each recipe, giving us what has become the

standard form. The style used by both women, that of a housewife sharing her

own experiences , was popular – enough so that the character of Mrs Beeton was

deliberately cultivated as a wise, motherly authority figure… despite Isabella

being around twenty-five when her Book of

Household Management was first published in 1861. Most of her recipes and

household advice, sad to say, was lifted from a variety of other sources – including

Eliza Acton, Alexis Soyer, and Mrs Raffald from the century before. Not that it

appeared to matter – the books sold well enough that Mrs Beeton stayed in print

for over 70 years (my copy of the book was borrowed from my mother’s shelf of

cookbooks) and Eliza Acton was cited as a major influence by none other than

Delia Smith.

The recipes the two women included in their

respective books range from ‘Curried Maccaroni’ to ‘Sweet Pickle of Melon

(Foreign receipt.)’, but there is also a strong emphasis on the value of plain

cooking and reducing waste that Hannah Glasse or Elizabeth Raffald might have

been proud of. Here’s one from Mrs Beeton for using up cold mutton, which also

make full use of the British love of gravy…

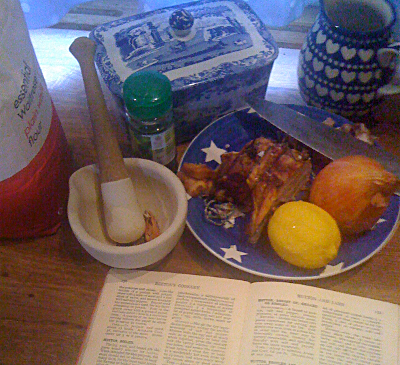

Not mentioned - grind the mace thoroughly before adding

(Transcribed from Mrs Beeton’s Cookery Book, 1914 edition.)

MUTTON COLLOPS

INGREDIENTS – 6 or 8 slices of cooked mutton, 2 shallots or 1 small onion finely chopped, ½ a teaspoonful or powdered mixed herbs, ½ a saltspoonful of mace, 1 dessertspoonful of flour, butter or fat for frying, ½ pint of gravy or stock, lemon-juice or vinegar, salt and pepper. METHOD – Cut the meat into round slices about 2 ½ inches in diameter. Mix together the shallot, herbs, mace, and a little pepper and salt, and spread this mixture on one side of the meat. Let it remain for1 hour, then fry quickly in hot butter or fat, taking care to cook the side covered with the mixture first. Remove and keep hot, sprinkle the flour on the bottom of the pan, which should contain no more fat than the flour will absorb, let it brown, then add the gravy or stock. Season to taste, boil gently for about 15 minutes, add a little lemon-juice or vinegar to flavour, and pour the sauce round the meat.

TIME – altogether, 1 ½ hours.

AVERAGE COST, about 1s. 8d.

SUFFICIENT, 1 lb. for 3 or 4 persons.

SEASONABLE at any time.

I'm not sure how much difference letting it sit for an hour makes.

This isn’t difficult to make, although

getting the onion mixture to stay on the meat when cooking is easier said than

done – I added a splash of water to help hold it together, and still had

trouble, but aside from untidiness this doesn’t matter too much. The meat I

used was cold lamb rather than mutton, since mutton is pretty uncommon these

days, but it’s from the same animal, so I wouldn’t worry too much. In fact,

this would also be delicious with cold beef – it’s hard to go wrong with fried

meat, onion and gravy.

Lemony gravy

Speaking of gravy – or stock, but I had

leftover gravy from the roast in any case, so I used that – I tried it with a

squeeze of lemon. It sounded peculiar, but it makes really good gravy – cutting

through the fatty meat very nicely. (And if your meat wasn’t fatty before, once

fried it will be.) Delicious and economical comfort food, great in chilly

weather.

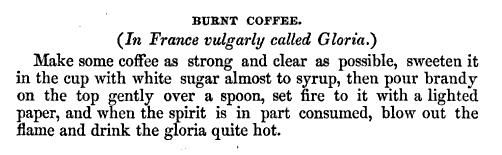

To finish us off with the Victorians, I

went back to aspirational cooking, for the middle classes keen to impress. Back

in 1782, a visitor to the country had lamented the British inability to make

coffee, and event Mrs Beeton warned that it was ‘difficult to make.’ But Eliza

Acton provided a few daring recipes, and being a coffee-lover myself, I gave

one a go.

'Vulgar' also meaning simply 'in the vernacular language'

Acton is not necessarily insulting the French here

Acton is not necessarily insulting the French here

It sounds very like a modern Irish Coffee –

hot coffee, with sugar and a spirit – only missing the cream. Warning bells

should go off, however, when reading how much sugar she suggests – ‘almost to

syrup’? Apparently the famous British love of sugar was still very much in

place. Well, I followed her instructions to the letter… several times over.

Try as I might, I could not get the brandy

to light. In the end, I heated the syrupy, highly-alcoholic coffee over the

stove to burn off some of the spirit before tasting, to little avail – it was

so sweet and strong it was virtually undrinkable.

Hopefully Eliza Acton had more success than I did. A sad end to an entertaining experiment, and to this stage of UK Food History! May my future forays into historical food be more successful that this incident - I can hardly wait.

Hopefully Eliza Acton had more success than I did. A sad end to an entertaining experiment, and to this stage of UK Food History! May my future forays into historical food be more successful that this incident - I can hardly wait.

No comments:

Post a Comment